Innovation

How are we innovative?

Below are innovative concepts that NUC implements in its projects and plans to reach a vision of livability, safety, health, and environmental stewardship.

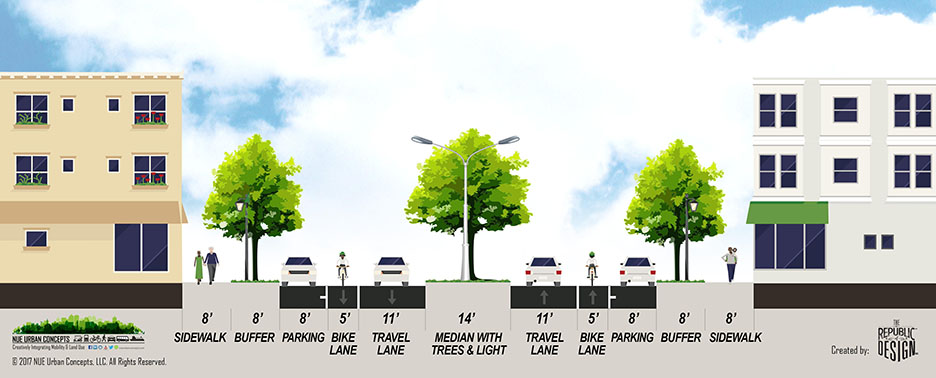

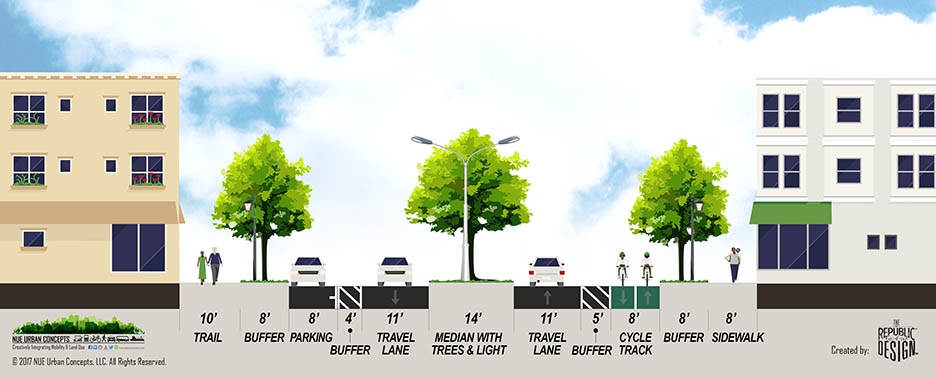

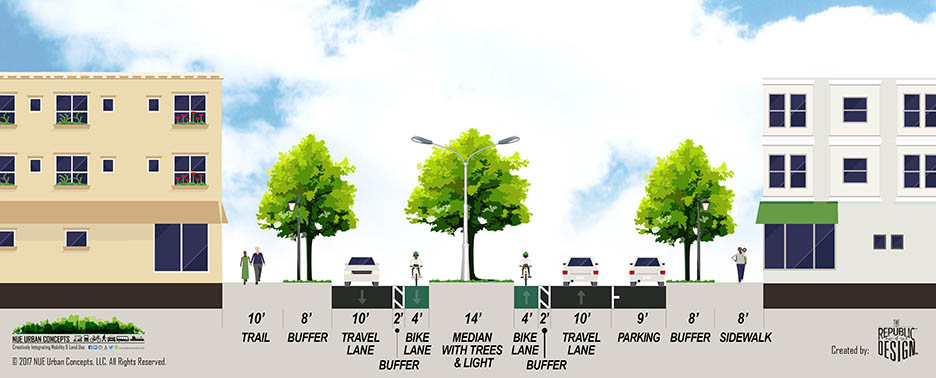

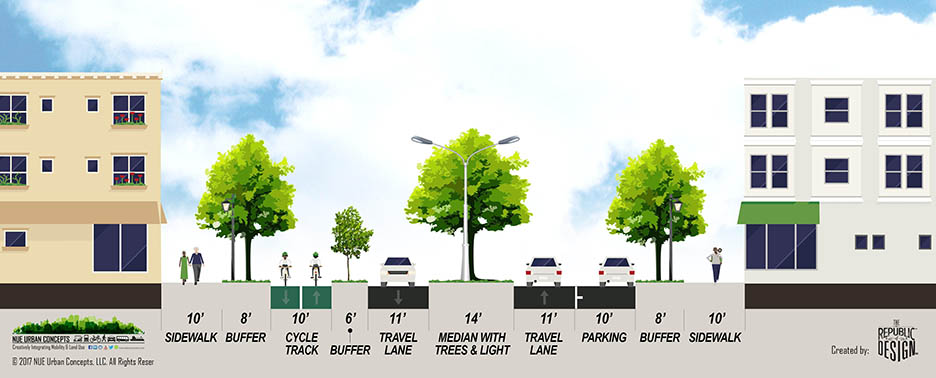

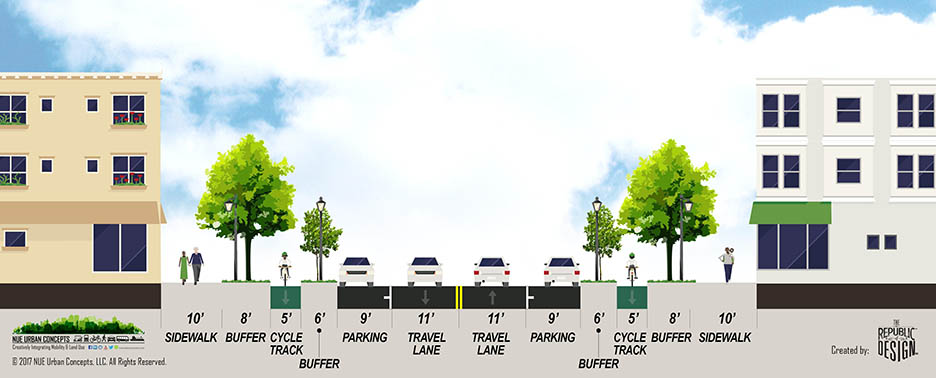

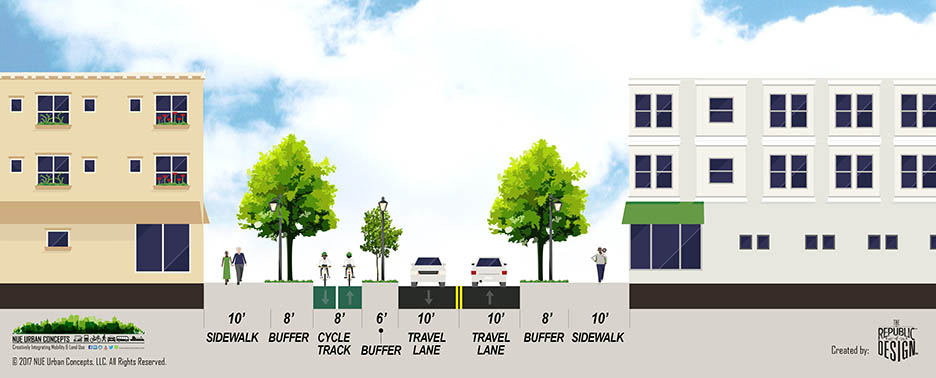

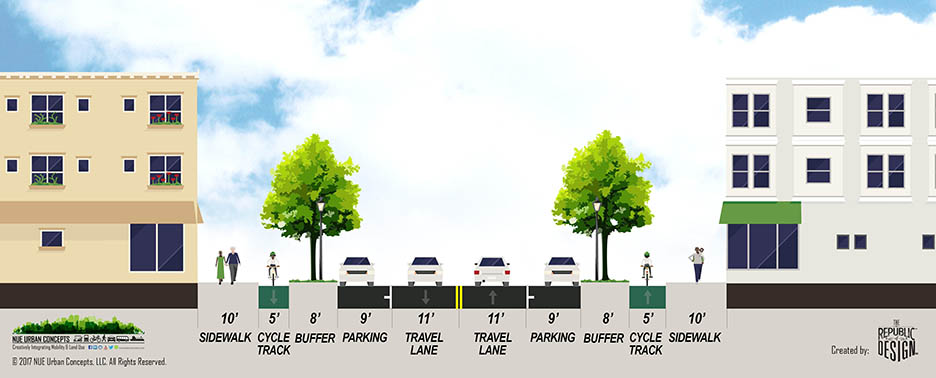

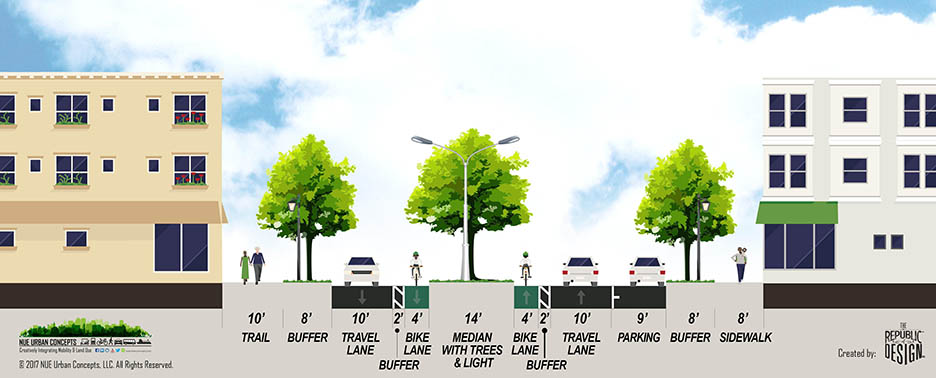

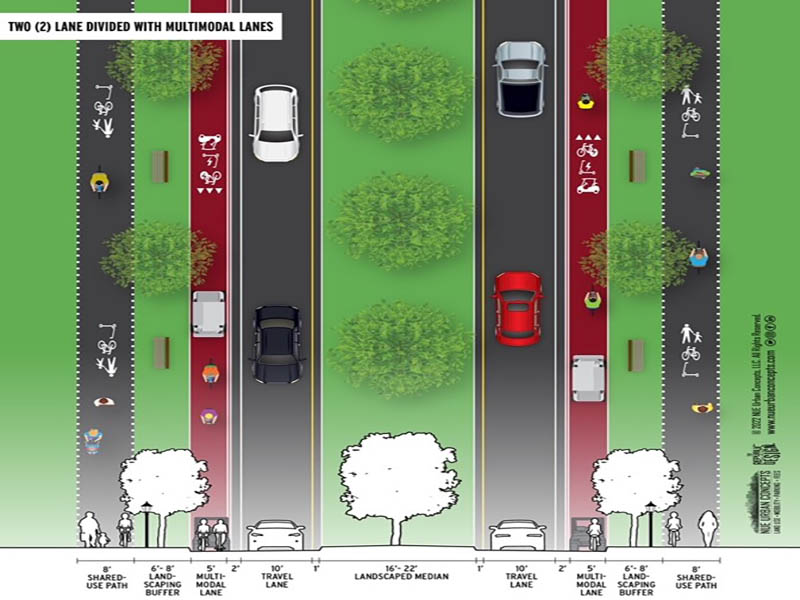

Complete Streets are streets that are designed and maintained in consideration of people of all ages and abilities, whether they are walking, biking, scooting, taking the bus, driving, or using wheelchairs. Complete Streets seek to improve mobility and safety for all users of the transportation system. There is no one size-fits-all design standard for Complete Streets; each Complete Street is unique and context sensitive.

In order to enable safe, convenient, and comfortable travel and access for all people, Complete Streets may include bicycle lanes / ways, multimodal lanes / ways, shared use paths, trails, traffic calming, landscaped medians / buffers, narrower travel lanes, roundabouts, road diets, curb extensions, high visibility crosswalks, and more.

Complete street design is an engineer-driven solution to provide accommodations for multiple modes of travel in defined spaces; with motorist safety, design speed and projected volume demands as the fundamental design elements.

Below is an example of a complete street:

A Complete Network is a network of Complete Streets that is connected, without gaps, and forms a well-integrated system between the various modes of transportation. A Completed Network provides communities the opportunity to better utilize its public space to offer safe and convenient transportation for all road users regardless of age, background, ability, or mode of travel.

Curbless Shared Streets feature speed limits of 15 miles per hour or less with all modes free to move about the street. On a Curbless Shared Street, no mode dominates, but the safety of the pedestrian and bicyclist is the fundamental starting point for design. Curbless Shared Streets are focused on person mobility, not motor vehicle mobility.

Curbless Shared Streets often include design elements such as special pavement markings, on-street parking, bollards, bicycle parking, street art, street furniture, streetscape, hardscape that work to cue drivers to slow down and drive safely.

Examples of Curbless Shared Streets in Florida include Clematis Street and Rosemary Avenue in West Palm Beach, and Aviles Street, Spanish Street, Cuna Street and Hypolita Street in St Augustine. Curbless Streets are starting to be incorporated into larger mixed-use developments as an alternative to an alleyway, street, or pedestrian only area.

Curbless Shared Streets feature speed limits of 15 miles per hour or less with all modes free to move about the street. On a Curbless Shared Street, no mode dominates, but the safety of the pedestrian and bicyclist is the fundamental starting point for design. Curbless Shared Streets are focused on person mobility, not motor vehicle mobility.

Curbless Shared Streets often include design elements such as special pavement markings, on-street parking, bollards, bicycle parking, street art, street furniture, streetscape, hardscape that work to cue drivers to slow down and drive safely.

Examples of Curbless Shared Streets in Florida include Clematis Street and Rosemary Avenue in West Palm Beach, and Aviles Street, Spanish Street, Cuna Street and Hypolita Street in St Augustine. Curbless Streets are starting to be incorporated into larger mixed-use developments as an alternative to an alleyway, street, or pedestrian only area.

TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT DISTRICTS

Developers and local governments are looking for creative ways to finance multi-modal transportation infrastructure. The establishment of a transportation improvement district (similar to tax increment financing or community redevelopment area districts) is a creative way to generate revenues and to promote a specific type of development pattern. The principal of NUE Urban Concepts played an integral role in the development of such a district in Alachua County.

Transportation improvement districts combined with mixed-use developments are a way for local governments and / or private developers to recapture increases in property tax revenue to fund multi-modal transportation improvements. Local governments can used TID’s to recapture increase in property taxes from upzoning properties adjacent to transit or in designated urban infill areas. Private developers can recoup some of the cost of providing public infrastructure, parking structures and/or the funding of transit service.

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT DISTRCITS & PUBLIC INFRASTURE FEE

Community Development Districts (CDDs) are special purpose local governments allowed by Florida Statute that provide limited governmental and fund and maintain infrastructure. CDD’s have the ability to issue bonds to fund infrastructure and to assesse development within the district to pay off the bonds. CDD’s may enact a Public Infrastructure Fee on retail sales within the district, similar to a sales tax, to pay for public infrastructure. The principal of NUE Urban Concepts helped with the establishment of the Celebration Pointe CDD and currently serves as its Chairman.

STATE INFRASTRUCTURE BANK LOAN

The State of Florida has established a State Infrastructure Bank (SIB) to provide competitive low interest loans to local governments and private developers to finance public infrastructure that benefits or relieves State Interstate System (SIS) facilities. NUE Urban Concepts helped the developer of Celebration Pointe obtain a low interest SIB loan to fund the SW 30th Bridge over Interstate 75. The SW 30th Bridge includes four travel lanes, the Archer Braid Trail, on-street bicycle lanes and a dedicated transit lane within the median.

IMPACT FEES

Impact fees are a traditional means of development mitigation used by many communities. However, most impact fees do not recognize the transportation benefits of mixed-use development or the reduced transportation impact of new development in urban areas.

The founder of NUE Urban Concepts developed the 1st Impact Fee that established a lower rate for Traditional Neighborhood Developments & developed a tiered impact fee rate for development within urban and rural areas.

MOBILITY FEES

Mobility Fees are an equitable and innovative alternative to traditional transportation concurrency and proportionate share that allows development to mitigate its impact to the transportation system through a one-time payment. Mobility Fees provide local governments with the flexibility to funding multi-modal transportation system improvements consistent with a Mobility Plan.

The Principal of NUE Urban Concepts has developed Mobility Fees for Alachua County, Osceola County and Sarasota County and is working with the Town Longboat Key, City of Venice, City of North Port, City of Altamonte Spring and the City of Maitland on development of Mobility Fees. The Mobility Fees are based upon Mobility Plans adopted to meet the unique travel demands of each community. The Mobility Fees are structured in such a manner as to assess lower Fees for mixed-use development, urban infill development and transit-oriented development.

- A goal to eliminate traffic fatalities and serious injuries; and

- A multifaceted strategy for how to reach this goal and provide safe, healthy, and equitable mobility for people of all ages and abilities.

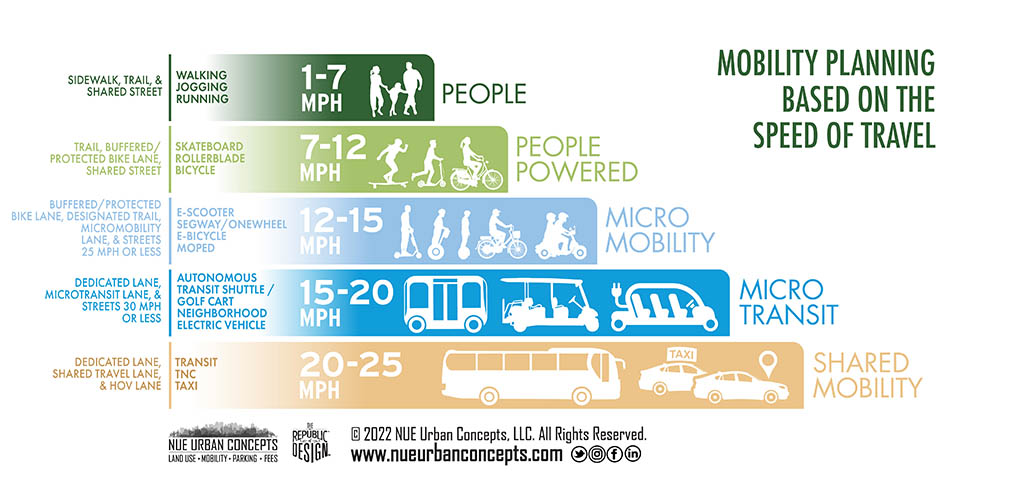

Transportation modes are often grouped into two categories, cars and “multimodal.” While slowing the speed of cars makes the biggest overall impact on street safety for other road users, there are significant speed differentials between different types of multimodal modes that can also sometimes create unsafe situations. Sidewalks and paths are designed to accommodate people bicycling, jogging, walking, or pushing a stroller at 1 to 7 miles per hour, while roads are designed to accommodate people driving cars between 20 and 50 miles per hour. This is a large speed difference that creates a “missing middle mode” in how cities currently build their transportation infrastructure. People riding electric bicycles or scooters, driving electric low speed vehicles or riding a transit circulator are moving between 10 and 20 miles per hour and are not currently accommodated on most major roads.

NUE Urban Concepts recommends infrastructure to accommodate multiple modes, traveling at varying speeds, that is appropriate and safe for each mode. This includes a variety of familiar multimodal facilities including sidewalks, bike lanes, shared-use paths, complete streets , and multi-use trails/greenways.

Multimodal Lanes and Multimodal Ways are designed to address the “missing middle modes” of electric micromobility (e.g., e-bike, e-scooter) devices and microtransit (e.g., golf carts) vehicles. A Multimodal Lane is an on-street facility, similar to a bicycle lane. A Multimodal Way is an off-street facility, similar to a shared-use path or a trail.

Multimodal lanes (on-street) widths vary from 6’ to 8’ for microtransit and microtransit vehicles (not including autonomous shuttles) and up to 10’ in width per direction when autonomous shuttles or other transit circulators are allowed.

Multimodal Ways (off-street) are typically between 5 feet and 12 feet wide (per direction) depending on which missing middle modes of travel are proposed to be accommodated. Ideally multimodal ways are at least six (6) feet wide and twelve (12) feet for bi-directional to provide for additional space for golf-carts. Five (5) feet and ten (10) feet widths are sufficient where golf carts are not a significant portion of the projected users of the multimodal way.

NUE Urban Concepts assists its clients in moving away from the traditional transportation planning practices and standards that prioritize driver convenience and vehicle flow by adopting multimodal standards that have an All Ages and Abilities approach.

NUE Urban Concepts assists its clients in moving away from the traditional transportation planning practices and standards that prioritize driver convenience and vehicle flow by adopting multimodal standards that have an All Ages and Abilities approach.

Level of Service (LOS) standards are traditional transportation service standards developed to help governments analyze operational traffic conditions and to allow for planning and prioritizing road capacity projects. What is lacking in this traditional approach is the ability to analyze conditions and provide services for people using multimodal mobility modes. While roadway LOS standards are based on road capacity to move cars, street QOS standards are intended to enhance mobility and safety for all users of the transportation system by prioritizing slower speeds for cars.

Street QOS standards are the inverse of roadway LOS standards in that as speed limits go down, street QOS goes up. The following graphic visualizes the Street Quality of Service (QOS) continuum and the type of mobility experience that each QOS standard provides. QOS standard A provides a street environment that prioritizes slower speeds, accessibility, and multimodal mobility for people. These streets not only help people reach their destinations, but can be destinations themselves that reclaim street space for spending time and offer a high level of social interaction. These are typically livelier streets that may include landscaping, public art, sitting and dining areas, and other elements that improve the sociability of the street. QOS A streets can be local or residential streets that require road users to travel slowly and actively engage with both the urban environment and other road users. As QOS goes down, there are more opportunities for conflict and road users must navigate through transitioning spaces that make multimodal design compromises to accommodate increased vehicle flow. On the other end of the continuum, street design for QOS E prioritizes higher speeds and vehicle travel between destinations resulting in a more isolated mobility experience.

Transportation research and planning practices have had a strong focus on work trips, disregarding the wide variety of trips taken for other daily needs. Over half of daily trips are less than three miles and more than a quarter of trips were less than one mile.

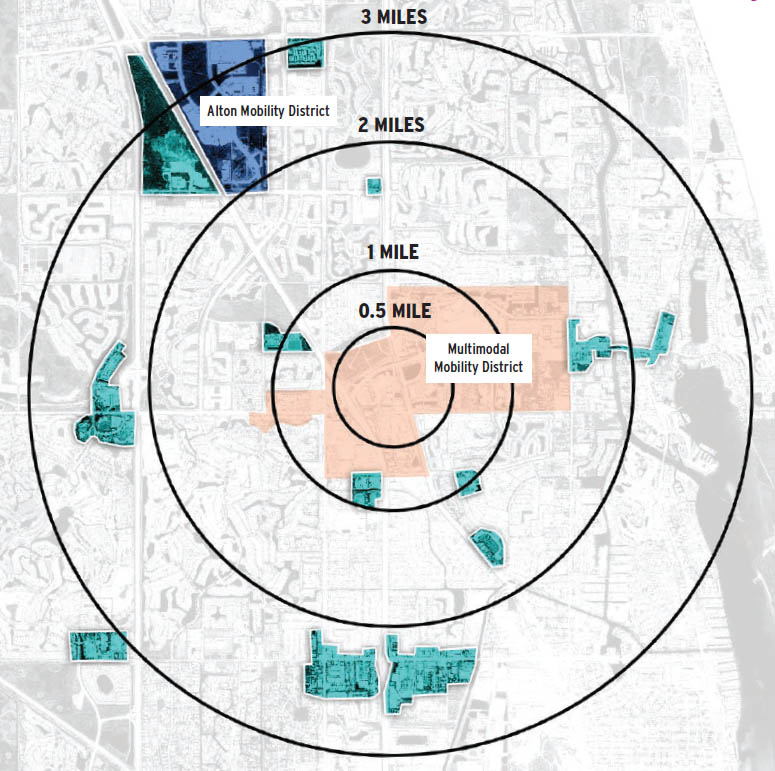

A 20 Minute City is a city with a vibrant mix of commercial, recreational, civic and residential establishments that are easy, safe and convenient for most residents and are within a one-mile walking distance (20-minutes), a three to four-mile bicycle ride (20-minutes) or a three to five-mile transit trip (20-minutes). These cities have a robust multimodal transportation system that includes sidewalks, paths, trails, bike lanes, and transit service.

In many cities, residential neighborhoods are already within three miles of a grocery store or commercial area, but low-density, suburban development makes it more attractive to use a car for these short trips. That’s why an approach to improving transportation must also be accompanied by sustainable land use policies and practices to compliment the infrastructure investments being made.

Transportation research and planning practices have had a strong focus on work trips, disregarding the wide variety of trips taken for other daily needs. Over half of daily trips are less than three miles and more than a quarter of trips were less than one mile.

A 20 Minute City is a city with a vibrant mix of commercial, recreational, civic and residential establishments that are easy, safe and convenient for most residents and are within a one-mile walking distance (20-minutes), a three to four-mile bicycle ride (20-minutes) or a three to five-mile transit trip (20-minutes). These cities have a robust multimodal transportation system that includes sidewalks, paths, trails, bike lanes, and transit service.

In many cities, residential neighborhoods are already within three miles of a grocery store or commercial area, but low-density, suburban development makes it more attractive to use a car for these short trips. That’s why an approach to improving transportation must also be accompanied by sustainable land use policies and practices to compliment the infrastructure investments being made.